信報 周永新 2009-09-17

回歸12年 多了22萬窮人

回歸十二年,香港窮人的數目是多了還是少了?這個數字,關心民生福利的當然重視,但窮人的數目反映的不僅是多少市民需要援助,還顯示很多社會現狀,包括國民收入的分配、不同家庭和年齡組合人士如何生活、政府給予低下層市民所需支援是否足夠等。總的一句,窮人數目的起跌,反映我們對弱小的愛心及社會對亟須幫助市民顯示的關愛。

政府統計處於去年八月發表了《一九九七年至二○○七年綜合社會保障援助計劃的統計數字》專題文章,我加上今年七月的綜援最新數字,作了一些分析。我這樣做,目的並不在看回歸以來多了多少窮人,而是正如以上說的,是想知道過去十二年,社會起了什麼變化?對收入不多的市民產生了什麼壓力?政府的綜援是否起着保障市民基本生活的作用?另外,對回歸以來貧窮情況多了了解,我再來討論人口政策,相信更能指出問題的癥結。

領綜援市民急增

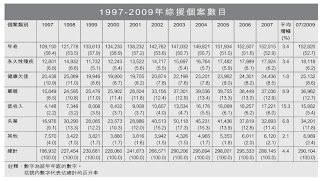

至於貧窮的定義,過往有不少討論,但最實際和有用的,應是指那些生活在綜援水平以下的市民、或更實際一點,是指那些正在領取綜援的市民,他們應是不折不扣的窮人。數字顯示,回歸以來,窮人的數目確實是多了,而且增幅遠超過人口的增長【表】。

二○○九年七月,綜援個案的數目達二十九萬宗,雖較二○○五年的最高數字少了八千宗,但較回歸那一年增加了十萬三千宗或百分之五十五。若以人數計算,二 ○○七年依靠綜援維生的市民共四十九萬六千多人,較一九九七年增加二十一萬四千人,增幅百分之七十五。換言之,領取綜援市民的人數在過去十二年(今年七月領取綜援的市民約五十萬,但我手頭沒有準確資料)急速增加,令香港現有七百萬人口中,超過百分之七必須依靠綜援過活。

為什麼這十二年來多了這麼多窮人?再看表一,若以個案類別分析:可見年老綜援個案雖仍佔一半以上,但比例明顯持續下降;其實,除去回歸最初幾年年老個案有較大增幅外(主因是董建華增加了年老綜援金額),自二○○○年開始,每年增加的個案只有三、四千宗,近兩三年且穩定在十五萬二千的數目-這是非常重要的數字,顯示愈來愈多退休人士早有預備,他們未必需要申請綜援。貧窮老人的數字若維持穩定,對安老政策有什麼影響?以後再討論。

年老與失業個案不可混合

綜援個案增幅最顯著的,依次是低收入、單親及失業。低收入個案九七年時是四千多宗,到了今年七月是一萬五千多宗,每年平均增幅約為百分之十五;單親綜援個案在九七年是一萬五千多宗,到了今年七月是三萬六千多宗,每年平均增幅約百分之九;失業個案變化較大,九七年時約有一萬七千宗,二○○三年時一度超過五萬宗,現在維持在三萬四千宗之間。

增幅最大的低收入、單親及失業個案,共通點是一旦符合資格領取綜援,家中多超過一個成員;這也解釋了為什麼過去十二年,綜援個案增加不到十萬宗,領取綜援的人數卻增加了超過二十萬。此三類個案的另一共通點,是家中都有成員可出外就業,但由於收入微薄、找不到工作、或須留在家中照顧幼童,所以他們才合資格領取綜援。

有工作能力的與沒有工作能力的(如年老、永久性殘疾、健康欠佳)應否在同一制度下接受援助?問題討論多年,我也曾提出把兩者分開:因受助者除都需要綜援維持基本生活外,其他就沒有什麼共通點了!舉個簡單例子:年老綜援個案多是單獨居住的長者,除金錢外,他們最需要的是護理等醫療服務,而失業和低收入綜援人士需要的,是提高他們技能的訓練及找到合適工作—處理這兩類性質迥然的個案怎可混在一起?

出生率低窮童比例升

再看領取綜援人士的年齡組合,資料顯示,回歸首十年,十五至五十九歲而領取綜援的增幅最大,從九七年的九萬四千多人增加至二○○七年的二十萬二千多人,即一倍有多;六十歲及以上的,十年來只增加五萬七千多人,低於老年人口增長的幅度;十五歲以下的兒童,增幅也頗顯著,特別在期間香港出生率偏低,所以比例上貧窮兒童多了。其實,多了單親家庭領取綜援,家中兒童也不情願地加入貧窮行列。

以上是從整體綜援數字看貧窮在香港特區成立以來所起的變化。總的來說,香港現有三十萬個家庭依靠綜援過活,其中三分之二屬於年老和傷病個案;若以人數計算,香港有五十萬領取綜援的窮人,其中二十一萬年齡介乎十五至五十九歲之間,是可以出外工作的,屬於人力資源的一部分。

這五十萬綜援窮人,背後都有令人傷感的故事;我們的社會能做的,就是給他們溫飽嗎?

ELIMINATION OF POVERTY:CHALLENGES AND ISLAMIC STRATEGIES*

Ismail SirageldinProfessor Emeritus, The Johns Hopkins University

The development of effective policies for poverty reduction and the monitoring of their progress and efficacy may not be feasible without a clear definition of poverty that could be measured with consistency across space and time. However, there are known difficult problems with defining and measuring poverty. There is no optimal definition or a measurement technique to compare poverty across countries or even within a country. Three decades ago, Martin Rein (1970: 46) identified three broad concepts of poverty that seem to encompass most of the difficulties associated with poverty analysis: subsistence, inequality, and externality. Subsistence is concerned with “minimum of provisions needed to maintain health and working capacity”(capabilities). Inequality is concerned with the “relative position of income groups toeach other.” Hence, the concept of poverty must be seen in the context of society asa whole. Poverty cannot be fully understood by isolating the poor and focusing on their behavior as a special group. It is equally important to understand the behavior of the rest of society especially the richer segment and the rich economies.Externality is concerned with the “social consequences of poverty for the rest of society rather than in terms of the needs of the poor. It is not so much the misery and plight of the poor but the discomfort and cost to the non-poor part of the community which is crucial to this view of poverty.” This latter view provides the political and social dimension of policies dealing with poverty. On the one hand, the poverty line serves as an index of the disutility to the community of the persistence of poverty. It reflects the extent of socio political commitment (cf. Smolensky 1966).On the other hand, it opens the door for the analysis of poverty as a social stratification problem,whether poverty is inherited across generations, or confined in geographic locations.The conceptualization of poverty has advanced since then, especially itsmacroeconomic linkages with distribution and growth. Recent advances in thisdirection have been helpful in elucidating poverty-related policies and strategies (cf.Ali and Elbadawi 1999, Squire 1999, and papers presented at the 1999 World BankStiglitz Summer Research Workshop on Poverty, and references cited there-in).However, understanding the sociopolitical environment and required institutionalcapacities on the local, national, or international levels continue to raise challengesand unsettled conceptual and measurements problems necessary for developingeffective policies and strategies.behavior, free-rider-type behavior, or the institutionalization of poverty. Thediscussion leads to exploring the role of Islam as a system of ethical axioms insupporting policies designed to eliminate poverty while enhance sustainable growthand equitable human development. Finally, the paper ends with concluding remarks. Each of the concepts outlined by Rein presents numerous conceptual, definitional,and measurement problems. Some continue to be part of the active research on thesubject as reflected, for example, in the cautionary endnotes on the data quality,conceptual, and measurement difficulties with data published recently on nationaland international poverty lines (2000 World Development Indicators: 65). It is notevident, for example, whether “the international poverty line measures the samedegree of need or deprivation across countries” (ibid). The same is true forcomparing poverty measures within countries, e.g., rural-urban comparisons. In anattempt to bring together four basic dimensions of human deprivation, the HumanDevelopment Report (1999) developed a multidimensional Human Poverty Index(HPI) based on health status, knowledge, economic provisioning, and socialinclusion. Although maintaining the same conceptual dimensions, the indicators ofthe HPI vary between the developing countries (HPI1) and the industrializedcountries (HPI2). For example, for the latter countries, income measure was used toindicate economic provisions while public provisioning was used for the developingcountries. The HPI provides useful cross-sectional and temporal internationalcomparisons. For the developing countries, the HPI1 reveals that, in 1997, humanpoverty ranges from a low of 2.6 percent in Barbados to a high of 65.5 percent inNiger. Thirty countries had a poverty index of at least 25 percent and fourteencountries with at least 35 percent. The incidence of poverty is widespread andconcentrated in Africa and south Asia. However, the HPI seems to suffer from thesame problems mentioned above, of data quality and consistency, and, being amacro indicator, the difficulty of interpreting the findings for policy analysis or theformulation of poverty-reduction strategies.